The costs of Carbon Capture and Storage

On 10th December of last year the UK government announced it had signed contracts for the support of the first two parts of the proposed carbon capture cluster in the north-east of England.[1] The projects to be funded are a new gas-fired power station with CCS, largely owned by BP, and a CO2 transmission network that takes the gas to subsurface storage in the North Sea. BP is also a major shareholder in this planned network. Two days later, the senior civil servant in DESNZ, the department responsible for developing the UK’s carbon capture capability, said that the details of the deals would be published ‘soon’.[2] He made this comment under questioning from a committee of the UK parliament.

When is ‘soon’? On 7th February, almost two months later, I wrote to DESNZ to ask if the terms of the contracts had been put into the public domain. The response came back rapidly; the department says that they will be published ‘in due course’, with no mention of any specific date.[3] It looks as though we may have to wait a long time to see the details of the schemes, including both the payments that will be made to the power station for capturing the CO2 and the pipeline network for transporting it. At the moment nobody has any idea how much these projects will cost energy bill payers and taxpayers.

Does this matter? Yes: the prospective subsidy for the UK’s CCS schemes is now set at almost £22bn and these first examples will set the cost expectations for all future developments. This note briefly looks at the what financial support is likely to have been agreed.

In summary, the subsidy agreed may be equivalent to doubling the cost of generating electricity in a gas-fired power station. The cost of gas with CCS could therefore be three times the price of electricity from a solar farm.

Background: the CCS projects.

The government has approved in principal two ‘clusters’ for CCS. One is on the north-east coast of England and the other on north-western side, spreading out into North Wales. Industries producing CO2 can apply for subsidies to collect and store the gas. The first contracts to be signed are for two projects in the north-east cluster: a new gas-fired power station and a separate transmission and storage network that takes the CO2 from the power station and future other sites.

· Net Zero Teesside Power (NZT Power)

The proposed power station will be located close to the mouth of the Tees estuary. The storage pipeline, engineered to offer a maximum of 4 million tonnes a year, will go offshore immediately to the depleted Endurance saline aquifer for permanent storage.

The design is for a 742 MW power station. If it operates all the time it will produce about 2.2 million tonnes of CO2 per year, and this figure is stated as the storage target. However more realistic expectations seem to be that the actual amount to be sequestered will be around 1 million tonnes. This suggests that the plant is expected to be operating about 50% of the time, generating an average of about 1-1.5% of current UK electricity needs.

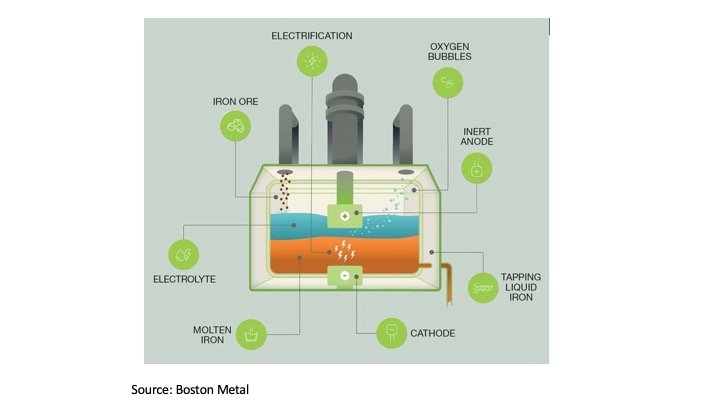

The new power station will use a carbon capture technology in Shell’s portfolio. Called CANSOLV, it operates at two existing power stations that use carbon capture. These two plants both burn coal as their fuel. No gas-fired power station uses CANSOLV and indeed NZT will probably be the first such plant worldwide to capture its emissions.

NZT Power is a joint venture between fossil fuel producers BP and Equinor. Construction will start in 2025 and is intended to be complete by 2028.

· Northern Endurance Partnership (NEP)

The transmission and storage network is owned by a consortium of BP, Equinor and TotalEnergies. The pipeline operated by NEP will run across the north east of England, passing close to some of the businesses that are applying for carbon capture subsidy. These entities include two blue hydrogen production plants as well as NZT.

The CO2 will be sent via a 145 km pipeline to permanent storage in the North Sea. The NEP has chosen the Endurance saline aquifer about 1000 metres below the surface.

· Types of remuneration agreed by government

We don’t yet know the numbers attached to the subsidies but we have been told the bases for payment.

The transmission and storage network will be allowed to charge a price for each tonne of CO2 stored. It will also benefit from payments for lack of use of its network. In other words, should the early CO2 production projects not start immediately the network is ready, NEP will be paid a fee for under-use. In addition, government is providing support for the costs of insuring against CO2 leakage. It also promises a payment to compensate NEP when the subsidy scheme has discontinued paying the per tonne of CO2 fee because the maximum financial support has been reached.

The power station has a completely separate payment scheme. This involves two mechanisms; one that pays the plant for being available for low carbon generation, even if no electricity is being produced and a second that makes a payment that is intended to cover the higher costs of operating CCS equipped power station. This variable payment will in effect be a top-up of the wholesale market price and will be calculated daily ‘benchmarked against a reference unabated plant’. The intention seems to be to pay awell-defined subsidy for each MWh of electricity produced bringing the CCS-equipped plant to financial equivalence with a similar power station with no CO2 collection.

How much will the CO2 collection and sequestration scheme cost?

The government talks of most of the additional bills being added to domestic and business electricity bills. The rest will be provided by general taxation.

CO2 capture in a power station uses substantial energy. This is used both in the action of catching the CO2 but also to generate the heat that drives off the CO2 from the chemicals that have captured it. In the process planned for NZT, a type of chemical called an amine will capture the gas. The amine is then taken to a chamber where it is heated and the CO2 released so that it can be pipelined to storage.

Very roughly, it will take about 1 MWh of energy (heat and electricity) to capture 1 tonne of CO2 at a gas-fired power station. We don’t know the exact quantity because CCS is not yet operating on a full-sized plant.

Estimates of the full cost of carbon capture, including the energy use, range between about £110 per tonne of CO2 and much higher numbers. The £110 figure is taken from a written submission by a group at Oxford University to the UK parliament committee enquiry mentioned in the first paragraph of this note.[4] The researchers write that this is ‘the industry’s most optimistic full chain cost projection’.

Other recent sources suggest higher figures. One research report suggests the cost may be as much as twice this level.[5]These figures will include a return on the large amounts of capital employed in building the capture facility, not just the operating cost.

A typical modern gas-fired power station produces a tonne of CO2 for each three megawatt hours of electricity output. The implication is therefore that carbon capture from the new NZT plant on the north-east coast will add about £37-£75 per MWh to the cost of electricity produced.

The recent announcement of support for the Drax power station in north-east England gives us some help determining how high this figure is. According to Simon Evans of Carbon Brief, estimates made by the UK government suggests an expectation of average wholesale prices of around £75-80 per MWh in future electricity markets.[6] These figures are before the price of carbon is applied.

Other sources have estimated lower figures for CCS but these earlier figures usually do not take into account recent increases in the expected cost of installing CCS equipment. Nor do they account for the inevitable premium arising from having to capture CO2 from the dilute concentrations in a gas-fired power station exhaust and transporting the gas a long distance to an offshore permanent storage site.

Typically, gas power stations emit an exhaust stream which is only about 3.5% CO2, a number far lower than most chemical processes and also well below the concentrations from a coal-fired power station. Capturing CO2 from a gas-fired power station is the most expensive way of reducing emissions from a static source.

What are the implications for the cost of power from the NZT plant?

Assuming that the proposed NZT power station typically delivers electricity at an average price of £75 per MWh, the CCS will add between about 50% and about 100% to the cost of the power. The total bill to customers will range from about £112 to approximately £150 per MWh.

These figures compared to costs of around £50 for onshore wind and solar.[7] So renewables are less than half the cost of gas with CCS. I am being probably too suspicious but perhaps this is the reason that the subsidy that BP and its partners have been awarded has not been made public.

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/contracts-signed-for-uks-first-carbon-capture-projects-in-teesside

[2] https://committees.parliament.uk/work/8576/carbon-capture-usage-and-storage/publications/oral-evidence/

[3] Personal communication from press office at DESNZ.

[4] https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/131665/pdf/

[5] Cost numbers obtained from ‘Curb Your Enthusiasm’, a report published by Carbon Tracker. https://carbontracker.org/reports/curb-your-enthusiasm/.

[6] Reference price estimate is taken from a BlueSky post by Simon Evans of Carbon Brief at https://bsky.app/profile/drsimevans.carbonbrief.org/post/3lhsuawsv4s26

[7] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6556027d046ed400148b99fe/electricity-generation-costs-2023.pdf. The figures given in this report are in 2021 prices and I have inflated them to current levels.